The air in 1960s Hong Kong crackled with a distinct energy – a potent mix of ambition, struggle, and bewildering speed. This wasn't just another decade; it was a crucible where the 1960s Hong Kong Social & Cultural Landscape was forged anew, transforming a bustling colonial port into a dynamic high-rise metropolis. Imagine a city bustling at the seams, doubling its factories, welcoming a flood of new faces, and suddenly tuning into its first free-to-air television broadcast. It was a time of seismic shifts, laying the very foundations for the global city we know today.

At a Glance: Hong Kong in the 1960s

- Economic Boom: Rapid industrialization, especially in textiles, created a powerful "Made in Hong Kong" brand and massive job growth across all sectors.

- Population Surge: A burgeoning, youthful population, heavily influenced by continuous refugee arrivals, reshaped traditional family life and fueled industrial labor demand.

- Urban Transformation: The skyline dramatically evolved from low-rise colonial buildings to a landscape dominated by high-rises, supported by ambitious public housing initiatives.

- Social Evolution: Women increasingly joined the workforce, traditional family structures were challenged, and workplaces often became de facto social and educational hubs.

- Educational Revolution: The government launched significant public education programs, leading to near-universal primary school attendance.

- Turbulent Times: The decade was marked by significant civil unrest (the Star Ferry and 1967 riots), devastating typhoons, and severe, politically charged water shortages.

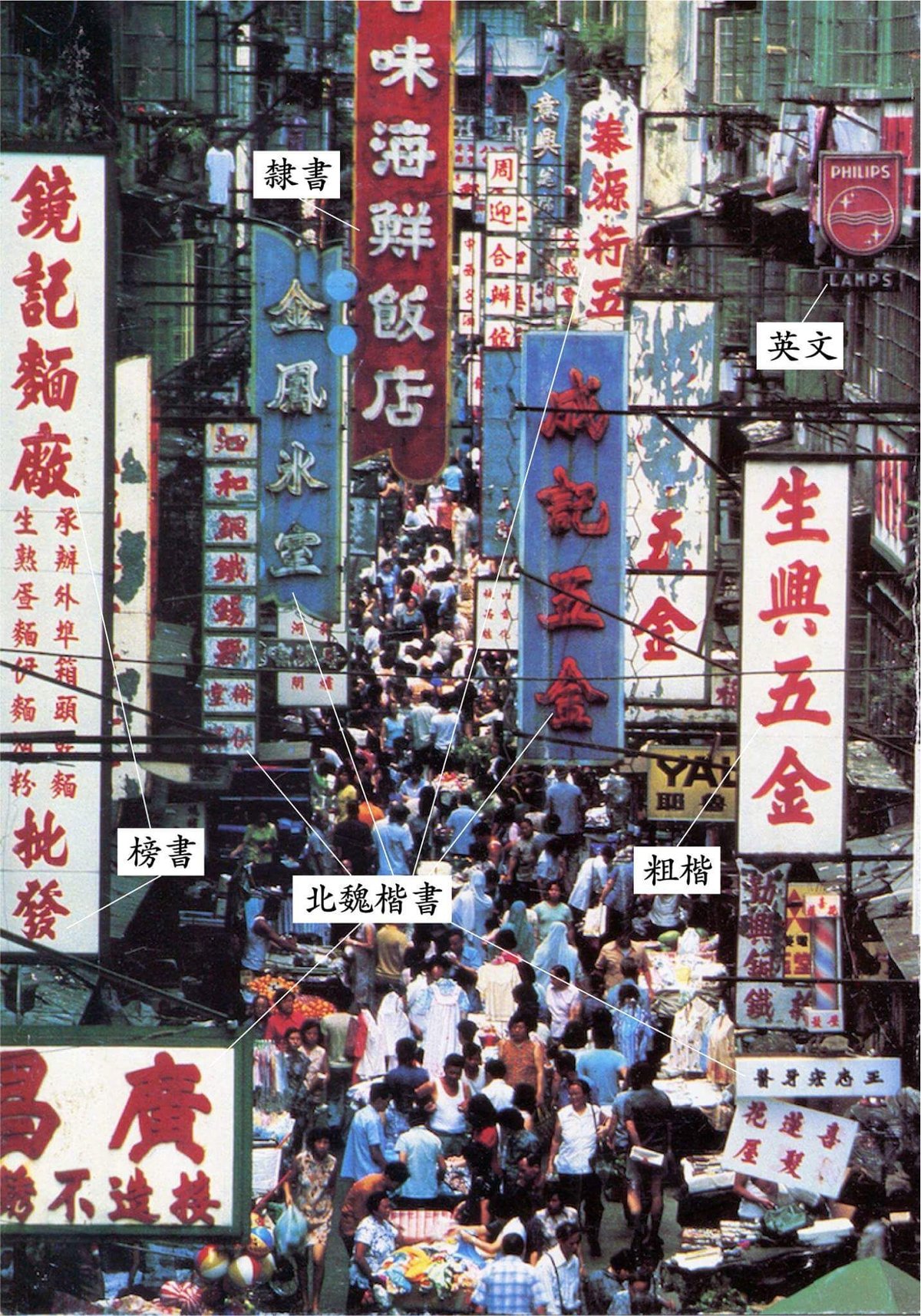

- Cultural Crossroads: Traditional Chinese cinema found a new counterpoint in the city’s first pop idol, broadcast television arrived, and community-building events like the Hong Kong Festival emerged.

- Global Footprint: Hong Kong played a unique role as a neutral stop for U.S. troops during the Vietnam War, enhancing its international profile.

Setting the Stage: Hong Kong's Leap into Modernity

The 1960s dawned on Hong Kong with a promise and a predicament. On one hand, it was an era of unprecedented economic acceleration, a pivotal turning point that would eventually cement its status as one of the "Four Asian Tigers" – alongside Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan. The city vibrated with growth, its wealth and population expanding at rates previously unimaginable. It was a place where futures were being built, quite literally, with new high-rises reaching for the sky. The colonial harbor was rapidly giving way to a burgeoning financial and cultural hub.

Yet, beneath this veneer of progress lay a complex tapestry of challenges. A continuous influx of refugees from mainland China swelled the population, straining resources but also injecting a vibrant, often desperate, workforce into the burgeoning industries. Social norms shifted under the weight of factory hours and urban density, while political tremors from the mainland occasionally spilled over, igniting periods of intense civil unrest. It was a decade where Hong Kong learned to adapt, innovate, and ultimately, define itself against a backdrop of relentless change and occasional turmoil.

The Engine of Prosperity: Hong Kong's Economic Ascent

If the 1960s were a turning point, then manufacturing was the engine driving Hong Kong's transformation. The colony experienced a veritable explosion in industrial output. Consider this: the number of registered factories surged from around 3,000 in the 1950s to a staggering 10,000 by the end of the 1960s. Similarly, the presence of foreign companies jumped from 300 to 500, a clear indicator of growing international confidence and investment in the nascent economy. This meant one thing for the people of Hong Kong: high demand for labor across virtually all sectors.

At the heart of this economic miracle was the textile industry. It wasn't just a sector; it was a way of life, supporting approximately 625,000 residents and famously operating 24 hours a day, seven days a week to meet global demand. What began as a production hub for cheap, low-grade items rapidly evolved. By 1968, "Made in Hong Kong" was becoming synonymous with quality, with textile products alone accounting for a remarkable 42% (or HKD $1.2 billion) of domestic exports to the UK. This transition from quantity to quality in manufacturing became a hallmark of Hong Kong's industrial prowess.

Even as per capita GDP in 1960 was initially low, comparable to countries like Peru, South Africa, or Greece, these widespread employment opportunities steadily improved living standards. The constant demand for workers across factories, construction sites, and burgeoning service industries meant a chance for upward mobility, despite wages that might seem modest by today's metrics. The entrepreneurial spirit was palpable, often starting in small, bustling factories that dotted the urban landscape, forming the backbone of this economic revolution.

A City of Youth: Population Dynamics and Evolving Social Fabric

By the 1960s, Hong Kong's population soared to an estimated 3 million, a remarkable figure given the city's geographical constraints. A striking demographic feature was its youthfulness: roughly half the population was under the age of 25, comprising a burgeoning baby boom generation. This youthful energy, combined with the continuous surge of refugees seeking a new life away from the turmoil in mainland China, created a unique social crucible. The newcomers added immensely to the labor force, but also stretched the city's resources and infrastructure to their limits.

Traditional Chinese family structures, deeply rooted in centuries of custom and often rural life, began to face unprecedented challenges in the dense, industrial urban environment. The demanding, often grueling, long factory hours meant that parents spent less time at home. Consequently, workplaces often morphed into "second homes," becoming unexpected hubs for social interaction, community building, and even informal education for many workers. This era also marked a significant shift in gender roles, with women increasingly joining the workforce, contributing vital income to their families and reshaping the domestic landscape from a purely patriarchal one.

Recognizing the importance of an educated populace for its industrial future and social stability, the government embarked on an ambitious public education program. They created over 300,000 new primary school places between 1954 and 1961, a colossal undertaking. This monumental effort paid off, with primary school attendance rates reaching an impressive 99.8% by 1966, laying the groundwork for future generations to climb the socio-economic ladder and contribute to the city's burgeoning professional class.

Building the Future: Urbanization and Infrastructure Development

The rapid population growth and economic expansion of the 1960s literally reshaped Hong Kong's skyline. The quaint, low-level colonial buildings that characterized much of the pre-war city began to give way to towering high-rises, symbolizing progress and a new era of vertical living. Iconic structures like the Prince's Building and the luxurious Mandarin Oriental hotel opened, further cementing Hong Kong's image as a modern, sophisticated city. Even earlier, the HSBC building, completed in 1935, had already set a precedent as Hong Kong's first air-conditioned building, hinting at the future comfort and technological aspirations of the city.

Construction wasn't confined to the central districts. The urban footprint expanded significantly, stretching west towards Tuen Mun and north into the once-rural Sha Tin valley, transforming agricultural lands into nascent urban centers ready for development. In 1969, the "Colony Outline Plan" formalized strategies for housing a million people, emphasizing the creation of low-cost public housing estates that would become a defining feature of Hong Kong's urban landscape. This visionary plan also set crucial guidelines for high-density construction, a practical necessity for a city with limited space.

Navigating this bustling city required robust transportation methods that combined the traditional with the emerging. The Star Ferry services remained absolutely essential for connecting Hong Kong Island to Kowloon, a vital link that predated and continued to serve as the primary route before the Cross-Harbour Tunnel was conceived. Rickshaws, though slowly fading from prominence, were still a common sight, offering rides (like a typical 50-cent journey from the Peninsula Hotel to the Star Ferry Pier) that spoke to a blend of old-world charm and urban necessity. The Peak Tram, having served residents and visitors with its scenic ascent since 1888, continued its operations. For daily sustenance, traditional wet markets remained the primary food source for most residents, offering fresh produce and a vibrant community atmosphere. Along the coast, sampans, small traditional Chinese boats, weren't just for transport; they served as mobile businesses and even homes for many, embodying the enduring maritime spirit of Hong Kong.

Through Storm and Strife: A Decade of Challenges

The transformative energy of the 1960s was not without its turbulence. Hong Kong found itself caught in a complex web of internal pressures and external influences. Politically, the decade was heavily shadowed by the chaotic events of the Cultural Revolution in mainland China, creating ideological divisions within the colony and periodically fanning the flames of dissent among pro-communist factions.

This external influence contributed to significant civil unrest within Hong Kong. In 1966, the city experienced riots sparked by a seemingly minor proposed Star Ferry fare increase, which quickly escalated. This initial wave of protest led to 20,000 signatures on a petition and over 1,800 arrests. The following year, the Hong Kong 1967 riots erupted, a more severe and prolonged challenge to British rule orchestrated by pro-communist leftists. This period of intense confrontation, marked by bombs, strikes, and violent clashes, only ended in December 1967 by direct order of Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai himself. Tragically, radio host Lam Bun was murdered during this turbulent time, a stark reminder of the decade's dangers and political volatility.

Beyond political upheaval, natural disasters tested the city's resilience. Typhoon Mary, on June 8, 1960, claimed 45 lives, injured 127, and destroyed an estimated 10,000 homes. Just two years later, Typhoon Wanda in 1962 was even more devastating, leaving 130 dead and 72,000 homeless, highlighting the vulnerability of the densely packed communities. Compounding these meteorological woes were severe droughts in 1963 and 1967. These prolonged dry spells, partly attributed to the global atmospheric effects of the 1963 Agung volcano eruption, led to extreme water restrictions – residents would often receive water for only four hours every four days. The irony was that these shortages were frequently exacerbated by China periodically turning off its water supply, a political lever that led to a crucial 1964 contract securing 15,000 gallons per day from China's East River. This resource vulnerability underscored Hong Kong's complex dependency on its larger neighbor.

A New Rhythm: Cultural Shifts and Global Connections

Amidst the economic and social currents, Hong Kong's cultural landscape also began to evolve, finding new expressions and influences. While Cantonese cinema continued to uphold traditional Chinese narratives and aesthetics, often through martial arts films and dramas, the decade also saw the emergence of its first true pop culture teen idol: Connie Chan Po-chu. Her electrifying performances captivated a youthful audience, signaling a nascent local entertainment scene that was beginning to forge its own identity, distinct from both mainland China and the West.

A monumental shift in media arrived in 1967 with the founding of TVB station, making Hong Kong's first free-over-the-air television broadcast. This brought a new dimension to daily life, offering entertainment, news, and a shared cultural experience directly into homes, quickly becoming a central part of the emerging popular culture. As the decade drew to a close, a conscious effort was made to channel public energy positively after the tumultuous 1967 riots. The first Hong Kong Festival, held from December 6-15, 1969, was a grand success, funded with HKD $4 million and attracting over 500,000 participants. It was a vibrant display of community and culture, aiming to heal, unite, and project a positive image of the city.

Beyond its borders, Hong Kong played a unique role on the international stage, particularly during the Vietnam War. The city became a frequent and popular stop for resting U.S. troops, perceived as a relatively neutral and welcoming zone offering respite from the conflict. This influx of foreign visitors further contributed to the city's cosmopolitan atmosphere and its growing reputation as an international hub for trade and leisure.

Domestically, the health and well-being of the rapidly growing population were also priorities. The executive council worked to revamp the medical system from 1960-1965, aiming to provide low-cost healthcare accessibility to more residents across the territory. This initiative proved timely, as the Hong Kong Flu in 1968 infected an estimated 15% of the population, highlighting the ongoing need for robust public health infrastructure in a fast-expanding city.

Echoes of a Pivotal Past: The Enduring Legacy

The 1960s were far more than just ten years on a calendar for Hong Kong; they were a foundational decade that irrevocably shaped the city's trajectory. From the factory floors buzzing with round-the-clock textile production to the towering public housing estates designed to shelter millions, every aspect of life underwent profound transformation. The scars of civil unrest and natural disaster served as harsh lessons, fostering a resilient, adaptive spirit that would come to define the city for generations.

The blend of rapid economic development, mass migration, urbanization, and a burgeoning local culture set the stage for Hong Kong's continued rise as a global player. The decisions made and challenges overcome during this period laid the groundwork for the modern, vibrant, and incredibly complex city we recognize today. To truly appreciate its present, one must look back at the dramatic metamorphosis of the 1960s Hong Kong Social & Cultural Landscape. It's a story of resilience, ambition, and the relentless pursuit of a better future, echoes of which can still be felt in the city's art, its architecture, and even in the nostalgic portrayal of a bygone era, perhaps best captured in the cinematic elegance of something like In the Mood for Love. This pivotal decade didn't just change Hong Kong; it forged its very identity.